Seeking Gods and Fulfilment through the Occasional Rap, Ethno-electronica, Synths and Drum-loops: Borrowing from Indigenous Worlds

by Dk. Siti Zulaikha Pg Hj Ishak.

In 1971, French ethnomusicologist Hugo Zemp recorded a traditional folk lullaby on the shores of Filunui, Solomon Islands. The song, Rorogwela, was sung by a young woman named Afunakwa.

“Sasi sasi ae taro taro amu,

Ko tratado tratado boroi tika oli oe lau

Tika gwao oe lau koro inomaena

Sasi sasi ae na ga koro mi koro

Mada maena mada ni ada I dai

I dai tabesau I tebetai nau mouri

Tabe tu wane initoa te he rofia”

Little brother, little brother, hush now, hush now,

You keep crying, but there’s no one else to carry you

No one else to take care of you, we’re both orphans now

From the island of the dead, their spirit will look after us

And take care of us like royalty,

With all the wisdom they’ll find there.

Two years after the recording, UNESCO released the song under the album Fataleka and Baegu Music. It failed to receive worldwide recognition, and the voice of Afunakwa disappeared under the turbulent waves of the same blue seas from which it came from. A few decades later, procurers of Deep Forest debut album listened through their Walkmans, the first track solemnly announcing; “somewhere, deep in the jungle, are living some little men and women. They are our past, and maybe, maybe they are our future”, before giving way to feverish synths, drumloops and ambient electronica. Refined by years under the sea, Afunakwa’s voice resurfaced in one of the tracks, reconfigured by French duo Michel Sanchez and Eric Mouquet. Three million copies of Sweet Lullaby were sold, and across the world, people crooned Afunakwa’s vocalizations without knowing any of the original words. The suggestive rhythmic, harmonic and textual contrast between modern and ethnic elements fused cultures of the globe in a new, hybrid expressions of world music, bringing with it refugees from the worlds of jazz, folk, rock and classical.

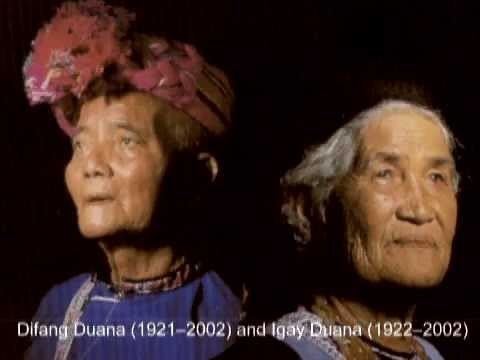

The musical expressions of native communities tied with ancient cultural connotations may not be simple notes to bop your head to: they represent a sophisticated articulation of the social and historical contexts of the people. At best, it allows for mobilization and constitution of entire ethnic consciousness as a revolutionary act of cultural preservation. The unique songs created from drowned lands hold their stories of old Gods and progresses of communities, ensuring great patterns remain. And yet, it was not too long ago that the voices of farmers, Kuo Hsiuo-chu and Kuo Ying-nan echoed through stereos worldwide during the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, hidden under the controversial doctoring of the renowned Enigma label, produced by Michael Cretu. Many assumed the warbled vocals of the pair to be extracted from deep jungles of the tropic; but the song ‘Return To Innocence’ samples Palang or the ‘Jubilant Drinking Song’ of the indigenous Ami people of Taiwan. The failure to give recognition to the singers and the community posed a dark risk of eradicating their identity as a whole. After the dust has settled, the Jubilant Drinking Song was not merely a simple folk song of the villages of Taiwan’s eastern valley anymore; Palang represented a central symbol of Amis’ ethnic identity to the contemporary international world.

Yet, undeniably, the fulfilment that ethno-electronic new-age albums gave to its listeners were remarkable, but largely dismissive of such indigenous triumphs. Generations that were growing increasingly disconnected from their own indigenous cultures began to find comfort in between the beats of new ambient world music. Many other contributors to the genre began to inject Native American, Sanskrit, and Tibetan chants to accompany the instrumentals. At the peak of new-age music, it seemed as though anything was possible; that cultures could come together in a kind of transnational tribalism with the rest of the world. Except, of course, the meaning of the original indigenous samples was continuously eradicated and lost in transmission despite global reception. More often than not, recollections of songs such as those created by Deep Forest evoke memories associated with the advertisements that use the music, and personal stories manifested by the listeners. It is of no surprise that it is critiqued as ‘moronic convergence’ by Richard Blow (1988).

This hybridization of ethnic and contemporary music gave birth to the conception of a skewed reality which allows for simultaneous concealing and revealing of cultural histories that are now intertwining fact and fantasy to create a place that never was. In other words, the issue balances on thin strands of two opposites – cultural appropriation or eradication at its worst, or strong indigenous representation at its best. Groups such as A Tribe Called Red, led by First Nation artists, calls for connection between its listeners and their ancestors by heavily infusing modern elements – synths, beats, even rap – with traditional musical elements. ‘R.E.D’, performed by ATCR, rapper Yasiin Bey, Narcy and Black Bear remain one of their most successful songs worldwide. Yasiin Bey opens up the song with the Muslim call “Bismillah’, followed by an utterance of ‘Hallelujah’ halfway through, accompanied by Native American chants in the background throughout. The song invites the listener to cut through material religions despite trauma and reunite, and the reception of the track garnered support from non-native communities, though it sings feverishly against colonisation and erosion of First Nation rights. In contexts such as these, where does the intersection of cultural appropriation and representation meet?

Fascinatingly enough, non-indigenous people often defend reproduced music that ‘borrows’ from indigenous cultures on this very foundation; that ‘nothing is created in vacuum’ and ‘concepts within life experiences are universal’. Music reflects the mood of an existing civilisation, and the new age’s popularity illustrates a collective need of people worldwide to escape to an alternate reality, connect, and heal together. The confused cultural representations in new-age music that emerge from stories or political plights felt by native communities’ transports listeners to a strange and ambiguous third space that suspends from found and fabricated ephemeras, from the magical and mundane, specific and generic and fiction and fantasy. And yet, our era is dominated by this world of specific and vagueness, creating false memories that become a mask to conceal landscapes of rich cultural possibilities from the past and into the present, not vague but specific and placed. It is a muddled reality that is experienced by many indigenous communities worldwide. In the contemporary climate of today, many seek for a connection with something transcendental and ‘otherworldly’, be it the Creator, the universe, nature, or even ancestral roots. This seeking of spirituality are the vignettes of everyday life, and many find a sense of connectedness through the fabric of songs, and a consequential peacefulness that transcends melody or rhythm.

So is the complexity in trivialising and distorting the ways of life for the indigenous communities; to make way for the new of wave of spiritual seeking, shared grief and the need for fulfilment. As described by Hall (2008), ‘the core metaphor guiding New Age is organic rather than mechanical; focusing on processes rather than products on a continual learning experience.’ So by all means, let’s process it all, but continue to question it all.

To ‘glorify’/’defacate’ on someone else’s culture and creating our own spin to it — how bad is it?

If it helps one feel less lonely, to be surrounded by ambiguous worldly presence in the musical arrangements — how do we measure its truthful damage?

If it fills oneself with hot grains of fulfilment and peace that causes reflection of one’s spiritual existence —

where do we draw the line?

Sweet Lullaby by Deep Forest: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lIF5EEneWEU

Rorogwela by Afunakwa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EntqjMonf9k

Return to Innocence by Enigma: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rk_sAHh9s08

Jubilant Drinking Song by Kuo Hsiuo-chu and Kuo Ying-nan: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uROdVAV1zQo

Blow, Richard. (1998). Moronic Convergence: The Moral and Spiritual Emptiness of New Age. The New Republic. Jan. 25, pp. 26-28