Damming of Himalayan River Basin and the Hegemonic Force of China: Water Grabbing through the Lens of Political Ecology

by Dk. Siti Zulaikha Pg Hj Ishak for Monash, 2018.

Water works in a tumultuous, eager system, powered by the sun, rushing from the sea, to the clouds, to the rivers, to the sea and back. Much of our water, to use a common but curious term, has been developed. In our lifetime, we have developed thousands of huge lakes, some more than a hundred miles long. We have turned dangerous rivers into staircases for ships. And everywhere, we have constrained the flood and transformed the ancient roar of rapids into the hum of electricity, changing the lives of those living in close proximity.

As water trickles elegantly through nations, socio-economic prosperity and environmental sustainability are promised for all, but transboundary water conflicts also spring up as a result of increasing water stress, bringing water to the forefront of political agenda of affected countries (Suhardiman, 2016). Water scarcity, increase in global food demand, desertification, sea level rise has led to a scrambling of the co-basin nations to find opportunity in investing for their future. A major river system spends about as much energy every half hour falling from its mountain sources to sea level as was released by the explosion of the Hiroshima bomb. To use that force – to develop it – human beings have met it head-on with our own eagerness for change and power.

The result is neither calm nor simple.

Still, the construction of dams is such an opportunity. The Himalayan River Basins represent a source of sustenance for roughly 1.3 billion people of almost 20% percent of the world’s population people; the water from the Himalayan mountain range feed large communities in India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, China, Bhutan and Nepal (Zerrouk, 2013). Its high elevational gradients, strong river velocity and high-water discharge is long established as an attractive energy-creating potential. As a result, mega dam construction on the rivers have grown exponentially in the last decade alongside demands for renewable hydropower production, in support of economic growth for all the countries within the region (Xu et al., 2008; Urban & Nordensvard, 2017). However, large dams that are built on trans-Himalayan rivers have long been the subject of controversy because of their magnitude, commonly irreversible social and environmental impacts and vulnerability to climate change (Zerrouk, 2013; Vidal, 2013, Arfanuzzaman, 2017 UNEP, 2012; Xu et al., 2008). Despite this, they remain a key energy priority that leads to unequal distribution of benefit along the national and local scales. This increasingly common phenomenon is known as water grabbing (Mehta et al., 2012). Water grabbing is described to be a situation whereby water rights are taken and reallocated by powerful actors for their own benefit, depriving the benefits to the existing local communities (Mehta et al., 2012). In conceptualizing the term, Mehta et al (2012) recognises two rough macro-dynamics of water grabbing: (i) the physical seizure of water for hydropower as well as (ii) the legal seizure of local people’s rights to access the water.

The privatisation and commoditisation of water in the Himalayan Rivers comes under such macro-dynamics. The hydropower plants could be reasoned to support agricultural, industrial and domestic use of the people in order to support economic development of developing regions such as India and China ((Sikder, 2013). Indeed, with construction pay checks and all that hydropower, economies blossomed. However, empirical studies have shown that dam building in the fragile socio-ecosystems have caused negative impacts to the livelihood of the local community (Sikder, 2013; Suhardiman, 2016; Vidal, 2013). Like a powerful medicine, its side effects can be devastating – a decline in agricultural and fishing yields over the last decade, adjustment or total removal of embedded socio- cultural practices, increase in foreign dam-workers and ultimately, a disempowering of the local community. Furthermore, permanent destruction of natural landscapes including large parts of the Tibetan plateau have been caused the construction of these large dams (Grumbine & Pandit, 2013; Matthew, 2013). To further complicate the water grabbing issue, the trans-boundary nature of the river leads to a power vacuum where hegemonic tendencies are continuously exhibited by nations, enabled by the lack of central authority regulating the tension along the river (Suhardiman, 2013; Mehta et al., 2012; Xu et al, 2008).

In all the complexities, where does the lens of capitalism fit in the the dimensions of water grabbing in political ecology?

II. A framework on water grabbing

Political ecology of water grabbing

Following an exponential increase in global concerns of food insecurity and fuel supplies, land acquisition for large-scale agricultural production have escalated in recent years (Xu et al., 2008; Zerrouk, 2013). The dimensions of this phenomenon, also known as land grabbing, have involved both public and private actors, including active participation of transnational corporations, national sovereign state and individual players through an obscuring of legal and illegal institutional processes (Mehta et al., 2012; Zeitoun & Warner, 2006). The implications of dispossession of land unto the communities has been adverse, stripping them of their rights to maintain their livelihoods with no potential mechanism of compensation and reallocation provided. Often, these projects are done under the guise of green agendas as a result of emerging climate change mitigation procedures (Pearce, 2013; Suhardiman, 2016; Vidal, 2013). Although land grabbing emphasizes heavily on the soil aspect of natural resources, the reality of ecosystems and its interconnectedness demand a re- evaluation of the natural resources that actually come into play; water dimensions of land grabbing are just as significant in ensuring the feasibility of a project (Mehta et al., 2012). Many authors in the water grabbing discourse, including Biswas (2011) explains that land and water are deeply intertwined in land grabbing frameworks, so much so that pre-requisites of land grabbing established by investors often prioritize the water conditions of the location before anything else. The fluid nature of water has led to multi-layered political complexities (Mehta et al., 2012). The hydrological processes that it partakes in results in its continuous movement throughout the river basin, affecting the communities living in the waterscapes. Thus, the flow of water reflects a flow of power and capital, resulting in the reconfiguration of socio-ecological arrangements over time (Mehta et al., 2012; Zeitoun & Warner, 2006; Matthew, 2013; Grumine & Pandit, 2013). Hence, applying a water lens help to simultaneously broaden our understanding of the impact extent of both land and water grabbing.

Nature of neo-liberalism and capitalism in water grabbing

In the event of water grabbing, communities that reside within the areas are often caught in the complexities of common property; that the deprivation of their rights to these natural resources that has long existed within their means of livelihood has led to their marginalisation (Mehta et al., 2012). The neo-liberalistic approach in environmental governance in the form of commodification and privatization of water has led to an escalation of conflicts within nations. The construction of Ilisu dam in Turkey have resulted in the resettlement of 25, 000 people and transferred exclusive access rights to hundreds and rivers and streams to private companies (Warner, 2012); the establishment of Tanzania’s Mafia Islands Marine park to spur co-management and community-based conservation management has become authoritarian in nature, closing off access to local residents despite traditional rights regimes that exist (Bejaminsen & Bryceson, 2012); and water fragmentation and privatisation of land to make way for a 20, 0000 sugarcane venture between the state and Mumias Sugar Company in Kenya’s Tana River Delta has led to the erosion of the state’s foundational pastoral systems (Berti et al., 1992). These case studies demonstrate how commodifying water in the scheme of water grabbing can legitimise the dispossession of vulnerable and marginalized communities and convert traditional rights to exclusive private rights.

At a fundamental level, water grabbing is a consequence of the global economic model of development that supports capitalism and the increasing control of natural resources through monetary valuation (Mehta et al., 2012; Milward-Hopkins, 2015; Pearce, 2013). While this process helps to prioritize and evaluate ecosystem services, these monetary valuation of is based on preferences weighted ultimately by purchasing power that prioritizes Western values over non-western values (such as indigenous ideals) (Milward-Hopkins, 2015). A few drivers of water grabbing have been identified; Franco et al (2012) alleges changing pattern in global food market as the biggest reason for land acquisition which requires water up to tenfold of normal demand, followed by the rise agrofuels and other renewable energy production, of which large amounts of water is exhausted in the production cycle (Urban & Nordensvard, 2017; Pearce, 2013; Sikder, 2013). Other drivers of water grabbing are the continued growth of large-scale mining ventures, privatization of water for its ecosystem services embedded in market-based management of natural resources and financialization of water (Sikder, 2013; Kumar et al., 2012). In nearly all of the cases, water grabbing is enabled by autonomous states that seek large investments, and find ways in bending the existing rules and regulations in ensuring that the project materialise (Grumine & Pandit, 2013; Bhatt et al., 2012). These large investments are provided by specific water-targeted investment funds and transnational corporations in the pursuit of securing a position in the current complex global crisis (Biswas, 2011; Guglielmo, 2018). Nevertheless, neo-liberalistic and capitalistic conceptualization of water grabbing triggers the corrosion stable water management, its socio- ecological systems and the transfer of power, rationalized in the name of ‘development’ (Mehta et al., 2012).

Water grabbing and transboundary issues

The geographical nature of large river basins transcends international boundaries and divisions; such examples include the Nile river of Africa which flows through Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, Egypt and Sudan; Indus river of South Asia which flows through India and Pakistan and the Mekong river of South East Asia which flows from the mountains of China and through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand and finally Cambodia (Arfanuzzaman, 2017). The management of transboundary rivers have become an important discourse in the social and political dimensions of global water demand in recent years; the lack of transboundary framework for water management is an issue that needs to be addressed more than ever in the light of increasing population demands and water tension (Matthew, 2013; Pearce, 2013). Without a central authority to develop a negotiation framework to regulate large rivers, the scramble to outcome other co-basin nations in first user rights (which takes effect after completion of a project) has reached climatic levels; this is the case for Yarlung Tsangpo Brahmaputra-Jamuna river in the Himalayas, with China attempting to build 40 mega dams along the river and India competing by listing 200 hydroelectric projects as a response (Sikder, 2013; Suhardiman, 2016). The socio-ecological stress that it could potentially release unto the landscape is colossal, destroying the livelihoods of millions of people in the waterscape. Aside from the lack of a negotiation framework, there are many interrelated political underpinnings of co-basin nation tension. In recent years, negotiation has been made even more difficult because of political mistrust, asymmetric power dimensions, opportunistic NGOs and rise of nationalism, all the while built upon historical tension that has long existed (Urban & Nordensvard; Vidal, 2013). Today, transboundary water disputes are often concluded by meeting the interest of one (or some) party, at the expense of others (Mehta et al., 2012; Pearce, 2013).

Hydro-hegemony framework

The conventional examination of transboundary water matters often focus on the technical dimension, downplaying the political underpinnings that form the foundation of the issues (Perce, 2013). The power asymmetry in water grabbing guides the hegemonic nature of the cases. Zeitoun et al (2012) proposes the framework of hydro-hegemony for the context of transboundary water conflicts to discuss the power complexities and conflicts that arise. Hydro-hegemony has no solid definition; rather it is any and all discourse in water conflict context that attempts to explain how some parties in manage to maintain their dominance (or power position) other than through illegal authoritarianism (Zeitoun et al., 2012). The purpose of the framework is to investigate the dominative form of power configured from water grabbing circumstances, and potential strategies that may permit a shifting from domination to collaboration (Zeitoun et al., 2012; Mehta et al., 2012; Guglielmo, 2018). The hydro-hegemon exploits the water resources of a basin as it pleases, accumulating the rights and benefits for itself at the expense of others. Although there are no formal acknowledgement or establishment of the hydro-hegemon, there soft power exists and allocates other nations on different levels (Vasudeva, 2012; Wagle et al., 2012; Biswas, 2011; Mehta et al., 2012). Nevertheless, such circumstances are often organically characterized by a reconfiguration and stability in the region due to the existence of a dominant authority (Mehta et al., 2012; Zeitoun & Warner, 2006). Consequently, such reconfiguration of power can lead to a positive, negative or a neutral outcome; positive whereby all parties benefit together; negative whereby outcomes do not satisfy at least one party involved, as well as neutral whereby there is a neutral compromise for all nations (Wagle et al., 2012; Warner, 2012; Pearce, 2013). The next section will apply the water grabbing framework in the Himalayan River Basin, represented through the micro-dynamic of dam construction and an evaluation of the hydro-hegemony of the area.

III. Water grabbing and basins managing in the Himalayan Rivers

Background on the Himalayan Basin

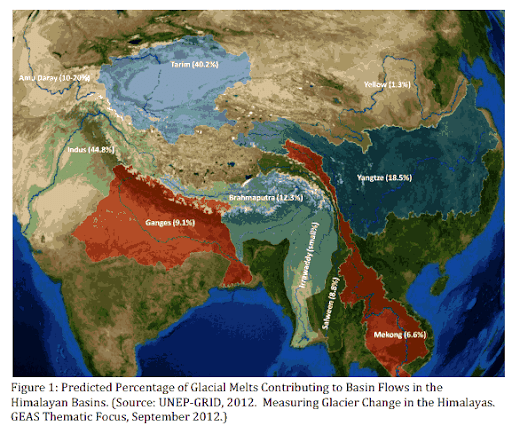

The Himalayan Basin flows from the Indus River Valley of the west to the Brahmaputra River Valley of the east, providing sustenance and livelihood to millions of people along the rivers and tributaries (Xu et al., 2008) The principle rivers of the Himalayan Region include the Amu Darya, Brahmaputra, Ganges, Indus, Irrawady, Mekong, Yangtze, Salween, Tarim and Yellow River; covering an area of 9 million km . (Xu et al., 2008) The extent of the Himalayan Basin can be seen in figure 1. The high mountains of the region strongly influence the climate circulation and patters, resulting in a varied topography endowed with rich biodiversity and ecosystems (Bhatt et al., 2012; Arfanuzzaman, 2017). Therefore, these rivers are lifeline to some of the most densely populated regions of the world, including states such as Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal (Affarnuzaman, 2017) . The communities depend on the waters from the river for a variety of domestic use, agriculture, hydropower as well as industrial use. However, the region is also one of the most fragile in the world, prone to seismic activity that results in soil erosion, heavy rains and flooding that affects the livelihood of millions (Sikder, 2013). This is further exacerbated by the poverty and inaccessibility to development services. In fact, poverty in the mountains is one average 5% more severe than the national average (Sikder, 2013)

Nature of neo-liberalism and capitalism in water grabbing

The huge volumes of water that pass through the rivers every year coupled with the large altitudinal drop contributes to the beneficial high hydropower potential that the Himalayan Basin holds, much of which remains untapped (Urban & Nordensvard, 2017; Strategic Foresight Group, 2018). The hydropower capacity in China alone reached 292 GW in 2014. In the last few years lone, dam construction has grown alongside increase in hydropower production (Wagle et al., 2012). In general, much of the reasoning behind the hydropower development was to fuel the growing need for energy power in the scramble of economic growth of countries like India and China, and in the goal of providing sustenance for agricultural, industrial and domestic use of the people (Vasudeva, 2012). However, the main investments were enabled by the financial concessions given by institutions such as the world bank (for environmentally positive purposes) and introduction of new policies by local governments which allows private companies to profit. The commodification of water in the Himalayan basin has underpinned the region’s neoliberal economic planning policies in luring investors. There are different incentives played out by different nations in the region to achieve this, with development of schemes to allow private companies to achieve legal title of the area in generating significant income (Wagle et al., 2012; Biswas, 2011; Grumbine & Pandit, 2013).

While many private companies achieved a position in this competition, many local communities were left with less favourable results (Sneddon, 2008). They are left in a vicious cycle of title and rights removal, poverty and failing livelihoods. In the case China, it is estimated that China is close to currently developing 350 hydropower projects in the region, fuelled by the Chinese government’s Going Out strategy and its recent One Belt, One Road policy which encourages overseas investments to access markets for Chinese goods and services (Vidal, 2013; Urban & Nordensvard, 2017). The fast-paced development has been scrutinized in its motives and mechanisms, questioned for its purpose in combining state- capital agendas and capitalist motives. Many argue that the ambiguous bundling of aid, trade and investments is done with intention to quietly remove conditionality in their investors, which may result in the large dismissal of poor governance in the recipient countries (Sneddon, 2008). This is demonstrated clearly in the proposal to develop hydropower on the Salween river, which will complicate an existing military conflict in Myanmar where the dam is proposed to be erected, albeit commendable justifications of renewable energy power generation (Zerrouk, 2013). Indeed, the poor and marginalized are often not taken into account in natural resource management, shedding light on the power asymmetries of the region where the people are left with no choice but to allow private companies to ‘grab’ their rights and livelihoods (Zerrouk, 2013). Therefore, the power asymmetry and lack of transparency amongst the states cause them to end up deeply entrenched in capitalist complexities instead of environmental prioritisation (Mehta et al., 2012).

Negative impacts of hydropower development and dam construction

As a whole, a total of 400 hydro-dams are planned to be constructed in the entire Himalayan River Basin, providing more than 160, 000MW of electricity (Strategic Group, 2018). This holds potential for concrete work that could completely bypass and exhaust rivers for long periods of time, cause massive blasting of existing ecosystems, mining of natural resources and permanent scarring of the aesthetic of natural ecosystems (Sikder, 2013). Although justifiable by its renewable characteristic, dams pose as a major threat to the minuscule remains of freshwater in the world, mediated by the loss of natural habitat and the species that reside within them, human or non-human (Sikder, 2013; Grumbine & Pandit, 2013). Furthermore, the spatial location of dams is often within seismically sensitive spots. The 7.9 earthquake which ravaged through the Sichuan Province of China caused the failure of the 511 ft Zipingu Dam in 2008 took the lives of 80, 000 people and left more than five million homeless. The dam released 315 million tonnes of water and caused massive flooding in the affected areas (Suhardiman, 2016).

Hydro-hegemony framework: Water grabbing and transboundary issues in the Himalayan Basin

It is evident that reaching the maximum potential for hydropower development in the Himalayan River Basin is entwined with political implications; the cooperation of north-east India and south-west China will generate 59 GW and 46 GW respectively; whereas Nepal will also achieve its hydropower potential if it cooperates with both India and China (Guglielmo, 2018, Kumar et al., 2012). On the other hand, Bangladesh will be able to purchase power from its neighbouring countries at a low cost, considering the short distance it will take to transport the energy (Xu et al., 2012). The intertwining of political agendas and needs other people of in each co-basin nation contributes to the fragility of the situation and the need for careful cooperation from each nation (Mehta et al., 2012; Zeitoun & Warner, 2006). Albeit much dialogue and discussion towards a collaboration in the Himalayan River Basins towards hydropower; it is observed that there is little inclination towards a ministerial level council (Vidal, 2013; Vasudeva, 2012). The paucity of a central framework creates a hegemonic interaction between the nations and an increase in transboundary tension. Water has become the new divide in politics; as lamented by (Vidal, 2013), it is effectively a “war without a shot being fired’’. Debatably, the situation could be categorized as ‘neutral, as there has yet to be open conflicts as a consequence of water grabbing, although it holds large potential of destabilizing the political constancy of the region. (Mehta et al., 2012).

China has been able to excel in in hydro-development with the introduction of many incentives from the central government; the national power industry has seen investments in both public and private parties as a result (Vasudeva, 2012; Vidal, 2013; Zerrouk, 2013). The Chinese control over the headwater in Tibetan plateau has granted it special privilege to control nearly 40% of the world’s source of livelihood has not come without controversy (Pearce, 2013; Urban & Nordensvard, 2017). In what is called the greatest water grab of history, China is categorised as a hegemonic force in the region because of its grabbing of the Brahmaputra river, exercising ‘soft’ power to other nations by creating projects that benefit only within the nation and cause detrimental effects to others (Zeitoun et al., 2011; Vidal, 2013). In the last few years, China and India has experienced high tension from the scrambling of land and development opportunities on the cross-border rivers of Yarlung-tsangpo and Brahmaputra (Biswas, 2011; Zeitoun et al., 2013). Tensions climaxed in 2000, when India experienced the death of 40 people and architectural destruction from a flood of the Brahamputra (Kumar et al., 2012; Suhardiman, 2016). Hydrological data was not publicized by the Chinese to inform of this potential calamity (Vidal, 2013). The act was provocative by China, causing diplomatic strain between the two nations. Instead of healing the strain, China is now gearing to develop four new hydroelectric dams on the Tibet river, potentially reducing the volume of flow downstream into India (Vidal, 2013). The hegemonic power of China now holds the influence to threaten India for political gain, through water blocking and inducing famine in the north-eastern region of India. This weaponizing of water in its water grabbing actions have given China leverage to ‘softly’ (i.e. without violence) encourage other nations to behave in a particular manner that it desires (Zeitoun et al., 2011).

Discussion and conclusion

The hydropower development in the Himalayan River basin remains an incredibly significant contributor the economy of all the co-basin nations involved, providing economic cushioning and food security to many of the people residing within the waterscapes. The potential for hydropower to serve as a solution in the global crisis of climate change and food insecurity is often used as justification in building dams along the river; however, the reality is much more complex and involves a myriad of political underpinning that leads to a hegemonic landscape. The policies and socio-political structuring of the nations are insufficient to frame a grand framework of trans-boundary water management in the region. Albeit the sceptical pushing of green agendas by every nation, it is evident that the responsibility and accountability of the projects are in question. The political ecology examination of the situation sheds light on the power struggle and marginalization of local communities in the name of ‘sustainable’ development and progress. India’s concern over China’s hydropower development lies not only in China’s spatial advantage of the Himalayan River Basin headwaters, but also on its political practice which does not encourage consultation with downstream states before, during and after a project. This contributes to a trans-border water issue on the foundation of water grabbing. China’s manipulation of transboundary river practices does not comply with international arrangements of water management (albeit the small amount that exist), leading other nations to believe that China functions on a zero-sum mentality in providing solely for its own security and prosperity at the risk of crippling other nations and causing insecurity throughout the region (Zeitoun et al., 2011). It maintains it hegemonic power by insisting a peaceful approach through negotiations and collaborative discussions. In contrast, China is also pointing fingers at India for utilizing the Brahmaputra waters at the expense of its neighbouring Bengalese interest.

The impacts of Chinese hegemony of the Himalayan River Basins through its endorsement of hydropower plans and dam construction in a large-scale water grabbing case have been shown to devastate not only the ecology within all of the co-basin nations, but also the power struggle of the local communities in accessing their inherent rights to access natural resources and the costs and benefits that are not shared equally among the countries. The complexities of the political dimensions within the region is much more complex, projected through ‘soft’ exertion of power and cold interactions between one another that could climax into a violent conflict of interest. Through this scrutiny, it can be observed that unequal distribution of dam advantages demands a re-evaluation of the simplistic façade of renewable energy and its effectiveness as a development strategy.

References:

Arfanuzzaman, M. (2017). Economics of transboundary water: an evaluation of glacier and snowpack-dependent river basin of the Hindu Kush Himalayan region. Water Policy, 20(1), pp.90-108.

Benjaminsen, T., & Bryceson, I. (2012). Conservation, green/blue grabbing and accumulation by dispossession in Tanzania. Journal Of Peasant Studies, 39(2), 335-355. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.667405

Berti, R., Chelazzi, L., Colombini, I., & Ercolini, A. (1992). Direction-finding ability in a mudskipper from the delta of the Tana river (Kenya). Tropical Zoology, 5(2), 219-228.doi: 10.1080/03946975.1992.10539194

Bhatt, J., Manish, K. and Pandit, M. (2012). Elevational Gradients in Fish Diversity in the Himalaya: Water Discharge Is the Key Driver of Distribution Patterns. PLoS ONE, 7(9), p.e46237.

Bingman, C. and Pitsvada, B. (1997). The Case for Contracting out and Privatization. Challenge, 40(6), pp.99-116.

Biswas, A. (2011). Cooperation or conflict in transboundary water management: case study of South Asia. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 56(4), 662-670. doi:10.1080/02626667.2011.572886

Grumbine, R. and Pandit, M. (2013). Threats from India’s Himalaya Dams. Science, 339(6115), pp.36-37.

Guglielmo, C. (2018). Interpreting Global Land and Water Grabbing through Two Rival Economic Paradigms. Academicus International Scientific Journal, 18, 42-52. doi:10.7336/academicus.2018.18.04

Matthew, R. (2013). Climate Change and Water Security in the Himalayan Region. Asia Policy, 16(1), 39-44. doi: 10.1353/asp.2013.0038

Millward-Hopkins, J. (2015). Natural capital, unnatural markets?. Wiley

Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 7(1), 13-22. doi: 10.1002/wcc.370

Pearce, F. (2013). Splash and grab: the global scramble for water.New

Scientist, 217(2906), 28-29. doi: 10.1016/s0262-4079(13)60548-5

Sikder, M. (2013). Environmental Degradation and Global Warming- Consequences of Himalayan Mega Dams: A Review. American Journal of Environmental Protection, 2(1),

Strategic Foresight Group (2018). Himalayan Solutions: Co-operation and Security in River Basins. [online] Strategic Foresight Group. Available at: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/127963/HimalayanSolutions.pdf [Accessed 2 Nov. 2018].

Suhardiman, D. (2016). The plan to dam Asia’s last free-flowing, international river. Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/the-plan-to-dam-asias-last-free-flowing-international-river-66346

UNEP. (2012). Measuring Glacier Change in the Himalayas. UNEP. Retrieved from https://na.unep.net/geas/getUNEPPageWithArticleIDScript.php?article_id=91

Urban, F., Siciliano, G., & Nordensvard, J. (2017). China’s dam-builders: their role in transboundary river management in South-East Asia. International Journal Of Water Resources Development, 34(5), 747-770. doi: 10.1080/07900627.2017.1329138

Vasudeva, C.P.K. (2012). Chinese Dams in Tibet and Diversion of Brahmaputra: Implications for India. Journal of the United States Institution of India. Vol XCLI (588). Retrieved from

Vidal, J. (2013). China and India ‘water grab’ dams put ecology of Himalayas in danger. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2013/aug/10/china-india-water-grab-dams-himalayas-danger

Wagle, S., Warghade, S., & Sathe, M. (2012). Exploiting Policy Obscurity for Legalising Water Grabbing in the Era of Economic Reform: The Case of Maharashtra, India. Water Alternatives, 5(2), pp 412-430

Warner, J. (2012). The struggle over Turkey’s Ilısu Dam: domestic and international security linkages.International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law And Economics, 12(3), 231-250. doi: 10.1007/s10784-012-9178-x

Xu, J., Grumbine, R.E., Shrestha, A., Eriksson, M., Yang, X., Wang, Y and Wilkes, A. (2008). The Melting Himalayas: Cascading Effeccts of Climate Change on Water, Biodiversity, and Livelihoods. Conservation Biology, 23 (3), 520-530.

Youatt, R. (2017). Personhood and the Rights of Nature: The New Subjects of Contemporary Earth Politics1. International Political Sociology, 11(1), pp.39-54.

Zeitoun, M., & Warner, J. (2006). Hydro-hegemony – a framework for analysis of trans-boundary water conflicts. Water Policy, 8(5), 435-460. doi: 10.2166/wp.2006.054

Zeitoun, M., Mirumachi, N., & Warner, J. (2011). Transboundary Water Interaction II: The Influence of ‘Soft Power’. International Environmental Agreements. Politics, law & economics, vol 11(2), pp. 159-178

Zerrouk, E. (2013). Water Grabbing/ Land Grabbing in Shared Water Basins the Case of Salween River Hatgyi Dam. Journal Of Water Resources And Ocean Science, 2(5), 68. doi: 10.11648/j.wros.20130205.13