Anxious Notes at Gardens by the Bay: Searching in Hybrid Spaces

“What am I here for?” (Ecclesiastes 12:13-14)

In the lush tapestry of urban wealth—spanning the remotest of wilderness to the vast city peripheries in between—to feel out of place a timeless facet of human existence.

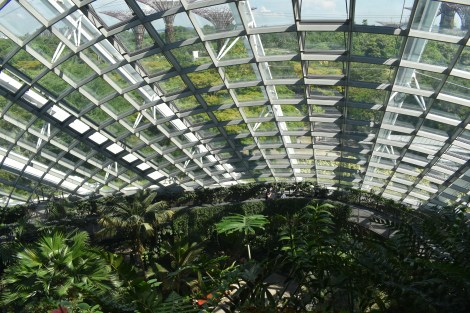

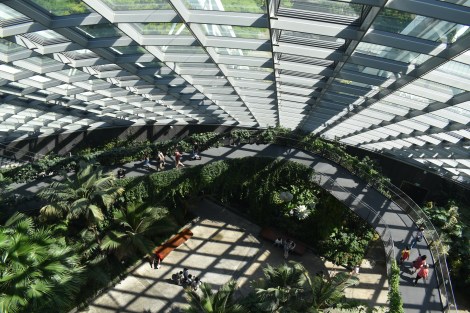

A woman ponders ahead at Singapore’s Cloud Forest canopy walk. More photos below.

A woman ponders ahead at Singapore’s Cloud Forest canopy walk. More photos below.

To question and seek, to yearn and desire, for a world familiar, or at least, not alien—is a simple tragedy of the human condition.

In the day’s whirlwind of steadfast capitalism, resource depletion, and political ruins, one’s sense of stability is fast depreciating into a delicious dream with which we have no teeth to chew into. In the vacuum of solace and nostalgia, hints of desolation stand to wreak havoc in one’s mind… We are reminded of the writings of Glenn Albercht et al (2007), where this anguish, suffered by people in the lived experience of the physical desolation of home, is coined as solastalgia.

Here, we witness the throes of place-connection being destroyed. Be it in the wake of unanticipated floods, extended droughts, or failure of a dam—it is a disorienting state—not quite nostalgia, because home exists still, but is in the process of being damaged and distorted. Such a reality is so starkly ordinary that we cannot fault those who retreat into denial; distancing oneself feels like a more accessible refuge. But as climate change deepens its impact worldwide—and deepen it will—solastalgia may well become an enduring household condition. And then, what?

From intangible dimensions of solastalgia, we step timidly with the onset of econostalgia.

In this state, home ceases to be.

Displacement goes hand-in-hand with the desire to return to environmental circumstances which have been irreversibly erased. Worse yet, it ushers in an anxious haze of defeat and reluctant acceptance of whatever solutions may stumble forth. Eco-anxiety has emerged as a universal phenomenon—a term that encapsulates the profound sorrow, pain, and even betrayal we experience in facing the environmental crisis. These emotions can no longer be dismissed as mere anomalies. When overwhelmed by the existential weight of environmental degradation, people often resort to various coping mechanisms. In a recent workshop on eco-anxiety versus eco solidarity for NUS, the lead scientist for Environment and Climate of IPUR, Dr. Olivia Jensen expressed the alarming number of women that have approached her and express how they were suffering from anorexia so that they may extract less resources from the earth, sacrificing sustenance of their own bodies.

Young people are the core demographic of this condition, and many feel as though they have been gaslit by the older generation of politicians – who can forget Greta Thunberg’s sharp lashing to Boris Johnson? “… this is not some expensive, politically correct, green act of bunny hugging” in retort to the prime minister’s previous use of the term in describing climate activism. It is a complicated state of fight. On the other hand, different forms of disavowal are much more common. People find ways to both know and not know at the same time. The vicious circle is unavoidable – from denial and disavowal, the problems worsen, breeding more anxiety and softened around the edges with more denial that feed emotional pressure. The numbing of emotional life is connected to what Lertzman (2015) calls environmental melancholia. People resort to a kind of anticipatory mourning where they try to break down in advance the emotional connection to certain things so that they do not have to suffer when they lose them. In the settling dust of environmental melancholy, people are placed in vulnerable states of acceptance for whatever solution may appear their way. It is just much simpler to not demand and enjoy the smallest morsels of hope.

In the ultimate city, gone are the days of living in primary forest ecologies, on riverbeds and coastal banks. Gone are days of harvesting sustenance from source. Gone too, are existential questions of why, and the desire to seek meaning and origin. And so, the understanding of the environment is continuously reconfigured – its etymology notwithstanding, the perception of environment is rather the medium in which we live, of which our being partakes and comes to identify. Within this environmental medium occur the activating forces of mind, eye, and hand, together with the perceptual features that engage these forces and elicit their reactions. We are inseparable performers now, no matter the stage. Every vestige of dualism must therefore be casted off here – the conscious body – as part of the spatio-temporal environment medium becomes the domain of human experience, the human world, the ground of human reality within which discriminations and distinctions are made. We live, then, in a dynamic nexus of interpenetrating forces to which we contribute and respond.

Do not say that I have a body, but rather I am my body, urged Marcel. And in similar tone, we can therefore say, we do not live in our environment, but that we are our environment. Just as we can consider the body an extrapolation from the unity of the human person, so can we regard the environment. This means that the concept of the environment must be altered to assimilate the lived body on the one hand and broadened to embrace the social in the other; the social, of which cultural meanings are embedded deep. Environmental comprehension is therefore a reciprocal world with the self, and a correlative study of the semiotics of environment to explore meanings that are inseparable from such features. The environment embraces cultural systems, which embraces person and place. In such fashion, a condition of either harmony or alienation arises with no solid bridge in the middle. This is because an environment can be shaped to encourage participation, or it can be structured to oppress, intimidate, control or brainwash a society. In these designed spaces, especially those which ambitiously mimic wilderness, it may fit not only the shape, movements and uses of the body, but also works with the conscious organism in the promising arc of expansion, development, and ultimately, fulfilment.

This is a goal that a deliberately articulated aesthetic can help accomplish – but how do we measure effective and ineffective aesthetic? In the egregious period of mass industrial failure, when do we know that a design may evolve beyond an architectural project where we may wander homeless and unwarmed, to one of home and hearth? Rousseau’s natural man has no place in a world that has been soiled wherever the human hand has touched – in therefore, the responsibility for shaping the human world lies in intelligent human action, but there is no easy or simple guide to found in nature or science. An ecological model may suggest the harmony for which we seek, but it is more a vision and a useful guide than a clear and straightforward answer. In the interplay of light and shadow, of color and texture, of pattern and movement, space and mass are made palpably present—and we, so activated by the stimuli, participate in a mutual exchange of action and response. We characterize this process of intimate involvement as aesthetic engagement, melting into continuities.

This is the aesthetic world, the world most real and most directly present to us. Aesthetic engagement recognizes the primacy of our immediate perceptual experience; one that is sensory yet coloured by the personal and cultural dimensions.

Yet, while these locations offer a mirroring of nature and aesthetic engagement, it is not a promise of tranquil space nor a refuge from the pressures of industrial urban life. Nevertheless, such designing features such as elevated walkways, narrow paths, and steppingstones may elicit feelings of apprehension or danger. It demands therefore, a close perceptual involvement from the visitor. These shapes influence the body’s reception – of the grandeur of oversize portals, of dips in the pathway which grips at our heart, and of unfamiliar mosaic of foreign flora. In the bending, squatting, sitting, or gawking, we sense with our entire bodies, not just with our eyes but with our ears, skin, legs, and muscle. Unfortunately, in these situations, it is inevitable that the large scale of such an ordered environment obscures biological uniqueness and difference. They expand the scope of an environment beyond the limits of sight so that the human body is lost in the vastness, and overwhelming ordered beauty. Few mysteries remain. Curiosity disappears with everything exposed. And in the worst-case scenario, an observational landscape can lead to immobility. With everything revealed at a quick glance, and $7 per admission ticket, there is little reason to press forward. In these spaces, aesthetics is often designed ‘trans-culturally’ – where a western observer may see a dry and uninteresting cacti ecosystem, an aboriginal eye discerns traditional travel routes with sacred places inhabited by ancestral spirits.

Solitude is almost a vestigial pleasure now that electronic entertainment can accompany us anywhere.

Yet, if not from God, are we not borrowing our planet from our children—as the saying goes—and if so, shouldn’t we deliver them in habitable shape? Neither Marxism nor Buddhism would dispute that contention—except, perhaps, in the shifting notion of what constitutes a habitable environment. If we consider ourselves not only preeminent among life forms but also preemptive in our actions—if most people care only for culinary calculations when unfarmed fish grow scarce, when roadless ridgelines lie devoid of windmills, when snowfields or meadowlarks disappear—then the few who do care and who wish to relax from the pell-mell continuum may have to obtain surround-sound film clips of Ansel Adams-type wilderness imagery for their wall-scale computer screens.

Jungle-striped yet captive-bred, the zoo cats endure as standard in modern zoos, much like pandas may become the norm after forests vanish—akin to replicated Tibetan monasteries that sport authentic facades and carefully painted exteriors, yet remain empty of monks.

________________________________

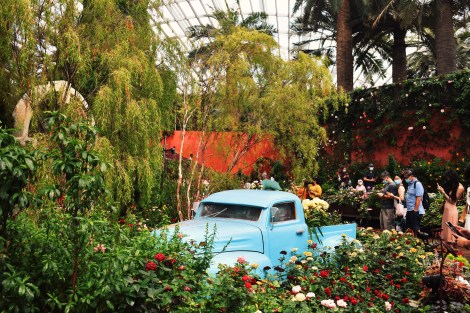

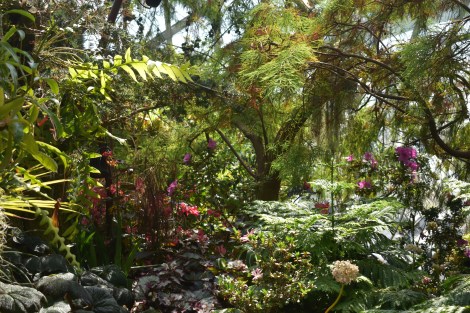

Some photos from the site.